I think a lot about that Spielbergian comparison, and I believe its validity lies mostly in the fact that Shyamalan’s early films, like Spielberg’s best, were novel enough in their mysticism to truly make an audience believe that there is a real sense of magic in the world. I grew up enamored by the colorful stories of superheroes and villains, driven by a good-evil dichotomy that was plainly, yet vibrantly seen, and captivating to a child for that reason. And now, as we can clearly see by the revitalization of the genre á la Marvel, it’s also captivating to millions of moviegoers.

Unbreakable, with its memorably somber stylization, is a film that represented a profound step in maturity for my manner of thinking about the world. The basic premise presents one of the superhero genre’s most intriguing origin stories, played to an audience high off “The Sixth Sense,” whose anticipation of a psychological thriller in the same vein by no means led them to anticipate the comic book tropes that Shyamalan plays with.

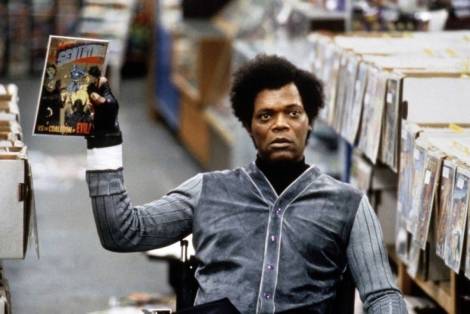

Bruce Willis plays a man named David Dunn (a name already comic-esque in its tongue-in-cheek alliteration), who is unscathed by an otherwise fatal train accident, and finds himself subject to the fantastical rationalizations of a physically handicapped comic book art dealer, Elijah, played by Samuel L. Jackson.

I first saw “Unbreakable” with my family when I was around 8 years old, right after it came out on VHS. Ever since, it’s never left my head. Forget what you think about the authenticity of superhero films that ground themselves in a grim, violent reality – what The Dark Knight films and Sin City did for the genre aside, there has never been a “comic book” film as well-made and subtly masterful as this one.

It was the audacity of Shyamalan’s gradual unveiling, the way in which he craftily draws back the curtain to reveal what his film “is,” that truly grabbed me (prior to having any real experience with Hitchcock). By unconventionally combining comic lore with psychological drama, what he created was wholly unique.

I clearly saw the reality of the film to be that of the “adult” world, hardly understood by an 8-year-old, but recognizable nonetheless, in its cold indifference. How then, could a character, a father, much the same age as my own, recognize himself to be something “special,” something superhuman, in a world like that? It never crossed my mind that a superhero could be conceived as someone other than a man in tights with a magical hammer from a whole other planet, or that he could perhaps be found in my own neighborhood, mowing the lawn on a Sunday afternoon. Alter ego is one thing, but not knowing your true identity is something else entirely.

Furthermore, how could such a man possibly muster the courage to be a hero, given the pervasive issues of everyday adult life (including ongoing problems with his wife, Audrey, played by Robin Wright), that, once again, were not thoroughly understood by me, but still undeniably present? And then, the scariest question of all – what then, would a real-lifesupervillain look like?

The film’s answers to these questions and its means of deciphering them have never been rivaled in their humane, ingenious way of sneaking their way into your head. Shyamalan’s presentation of what is undeniably our world, and its oddly befitting parallels to comic archetypes, never cease to amaze me. And for a genre I thought I had understood at such an early age, Unbreakable was an extraordinary awakening, an exercise in cinematic, out-of-the-box thinking that has influenced every creative work I’ve attempted since.

When you consider the evil that exists in our world, ranging from domestic abuse to wide-scale terrorism, there’s no other work I’ve experienced that’s planted a “comic book” hero in the middle of this reality with such authenticity.

I guess you could consider the next two paragraphs to contain “spoilers,” since they vaguely describe a particular scene. Depending on how much you know about the film already, this may/may not matter.

For me, the real crux of the film comes in a scene where David, eating breakfast at the kitchen table with his family, on what would otherwise be an ordinary day, slides a newspaper article toward his son, Joseph (played by Spencer Treat Clark), probably no older in the film than I was watching it. On the front page is an article depicting the first act of true heroism that Willis’ character has accomplished with his abilities, although he is not 100% discernible in the paper’s illustration.

His son knows. He doesn’t know, but he knows. And in a way he’s known all along, even before his father’s abilities became clear. Joseph’s eyes fill with tears, not just because he is faced with the realization that his father is indeed heroic, but with the fact there is magic in the world, a world filled with murderers, rapists, and constant terror. Perhaps in a few years he would be too cynical to believe this craziness; maybe, given the prior events in the film, his innocence has already worn away significantly. But in this moment, the presence of magic is undeniable. As a child, he knows that such magic, now finally acknowledged by his father, must truly exist. It remains one of the most beautiful scenes I’ve ever seen. We see belief come alive.

The presence of “magic,” the conceivability of something inexplicable, ultimately takes on a dual role in the film, as powers of the otherworldly are shown to be devices for both good and evil. But nobody said the privilege would come easy, did they? Free will is still the predominant factor of human existence, and surely as crucial to the hero-villain spectrum in comic books as it is to moral decision making in real life. Meanwhile, Unbreakable is surely unique in the manner that it also shows varying degrees of man’s pursuit of meaning, and how corruptibility and evil can befall those who search in the wrong places or via improper means.

Bridging this gap, between what appears to be thematically black-and-white tales of morality for children, and the grayish decision-making required of adults capable of both good and evil, is where the film finds singular thematic ground. In doing so, it brings out the substance of comic-grounded source material, while giving us a uniquely ethereal, deeply human drama.

In the roughly 16 years since Unbreakable was released, I’ve grown in a multitude of ways, in a variety of forms. I’ve never stopped learning more about the world and the unforgiving realities of adult life. I’ve also learned that being a cynic is easy; belief, in whatever form it takes in your life, is hard. Even at his schlockiest, Shyamalan has at least never lost that sense of youthful belief, in whatever genre-driven form. And despite all the crap he’s taken, Shyamalan’s still out there making movies. Despite their drop in quality, there’s something oddly commendable about that.

I’m happy to say that at 23, I’ve still held onto some sense of magic. Every time it disappears from my life for a short while, I’ve found there are many ways and means of recapturing it. But I take a special kind of solace in this one; in this idea that whenever I pack into a darkened theater with strangers or onto a sofa with people I know and adore, the magic can be found again. From his side of the camera, I think Shyamalan would agree. For me, the resilience of the film’s title takes on a special significance. The word “unbreakable” seems directly opposed to cynicism. What could be more Spielbergian than that?

It’s a good movie and if only M. Night made more of them. Nice post.

For sure. The path of his career has definitely been… interesting, to say the least. Thanks for reading!